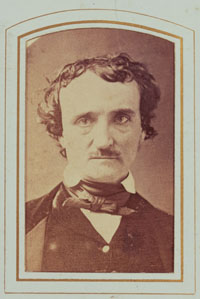

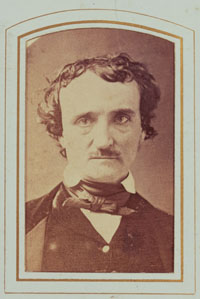

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (January 19, 1809, to October 7, 1849; flourished in Philadelphia, Summer, 1838, to April, 1844) needs little introduction, except maybe to say he is an adopted Philadelphian – claimed also by Baltimore, Boston, New York, Providence, Boston, and all of Virginia. He sojourned in Philadelphia from 1838 to 1844, where Brockden Brown inspired him, Doctor Bird outsold him, and George Lippard supported him, financially and professionally.

Those six years in the Quaker City were the most productive of his career. He worked as editor of two nationally prominent monthly magazines and published over thirty stories, including such Gothic classics as “The Pit and the Pendulum” and “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Here he met Charles Dickens, whose pet bird may have inspired “The Raven,” and here the poem took shape during bull-sessions with his best drinking companion, Henry Beck Hirst, who owned a Philadelphia bird store. He also invented the detective story while a Philadelphia resident, writing “Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841) and “The Mystery of Marie Roget” (1842-1843). Philadelphia editors continued to publish his best fiction, such as “The Cask of Amontillado” (1846), even after he left for New York in 1844.

Poe had long been prone to depression and alcoholism, and when he moved to seek backing for a magazine of his very own, his life spun out of control. He died in Baltimore, but almost all of his most haunting work emanated from Philadelphia – the very birthplace of America’s homegrown Gothic genres.

Left: Edgar Allan Poe. (New York, ca. 1870). Enlarged reproduction of an albumen print carte de visite copied from an 1849 daguerreotype. In May or June 1849, Poe had his portrait taken by an unidentified Lowell, Massachusetts, daguerreotypist for his patron Mrs. Annie Richmond. In 1876 she had a copy made, which was the basis of the carte de visite in the Library Company’s collection. The “Annie Daguerreotype” is one of eight known to have been made of Poe, and it shows him haggard and dissipated four months before his death. The original is now in the Getty Museum.

“There comes Poe with his raven, like Barnaby Rudge,

Three fifths of him genius and two fifths sheer fudge, . . .”

– James Russell Lowell, A Fable for Critics (1848)

_______________________________________________________________________________________

|

Charles Brockden Brown. Edgar Huntly; or, Memoirs of a Sleep-Walker. (Philadelphia, 1799). |

| |

|

|

“The Pit and the Pendulum.” In The Gift: a Christmas and New Year’s Present. MDCCCXLIII. (Philadelphia, 1842). Poe’s classic gothic story “The Pit and the Pendulum” was first published in this 1843 Philadelphia literary annual. Its principal American source was Brown’s novel Edgar Huntly. Brown lent Poe a hero, who believing he’s the victim of a tyrant, falls into a pit where he is deprived of sensory stimuli in the darkness and buried alive – almost everything but the pendulum. |

| |

|

|

Edgar A. Poe. Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque. (Philadelphia, 1840). This 1840 collection, published in Philadelphia, included Poe’s best work to that time, including “The Fall of the House of Usher.” He dedicated it to Col. William Drayton, who had befriended him when he served in the artillery brigade at Charleston’s Fort Moultrie in 1828. A decade later, Poe had long since been canned from the military by a West Point court-martial, and the colonel had moved to Philadelphia. Drayton tried to introduce Poe to Philadelphia society, but he did not fit in. |

| |

|

![P. [i.e., Edgar Allan Poe]. To Messrs. Bowen & Gossler, Editors of the “Columbia Spy.” (New-York, June 18 [1844]). Holograph manuscript letter signed.](images/th8.5a.jpg) |

P. [i.e., Edgar Allan Poe]. To Messrs. Bowen & Gossler, Editors of the “Columbia Spy.” (New-York, June 18 [1844]). Holograph manuscript letter signed. Even after he moved to the then not-so-Big Apple, just overtaking Philadelphia as America’s publishing center, Poe thought our town compared more than favorably with Manhattan. In this inflated letter to a small Pennsylvania newspaper (written for pay by the column inch), Poe says our Front Street is much longer than Broadway, and he criticizes New York City’s constabulary for botching a murder case he Frenchified into one of his best detective stories, “The Mystery of Marie Roget” (1842). |

| |

|

“… for they manage these matters wretchedly in New York. It is difficult to conceive anything more preposterous than the whole conduct, for example, of the Mary Rogers affair. . . . Not the least usual error, in such investigations, is the limiting of inquiry to the immediate, with total disregard of the collateral . . . events.” [This kind of thinking was the essence of Poe’s mysteries, what he liked to call “Ratiocination” – deducing the solution of a crime like all modern detectives since.] |

| |

|

“[Broadway] is no doubt a long street ; but we have many much longer in Philadelphia. If I do not greatly err, Front Street offers an unbroken line of houses for four miles, and is, unquestionably, the longest street in America, if not in the world.” |

| |

|

|

Edgar Allan Poe. Eureka: A Prose Poem. (New York, 1848). Loaned by the Free Library of Philadelphia. In some literary histories Lippard is mentioned only as Poe’s Philadelphia friend, who encouraged and took him in when he was down and out. Poe did what he could in gratitude for such help. A hint is this copy of Poe’s Eureka, one of only 500 printed, inscribed to Lippard. Lippard loved this kind of reading, an amalgam of mysticism and popular science. Kelpius and the Germantown Pietists were scientific mystics too, and they fascinated him more than anything in early Philadelphia history. |

The Raven

“The Raven.” By Edgar Allan Poe. (Conceived, Philadelphia, 1838-1844; published New York, 1845).

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore, –

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“‘Tis some visiter,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door –

Only this and nothing more.” …

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil! – prophet still, if bird or devil! –

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate, yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted –

On this home by Horror haunted – tell me truly, I implore –

Is there – is there balm in Gilead? – tell me – tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.” …

“Be that our sign of parting, bird or fiend!” I shrieked, upstarting –

“Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul has spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken! – quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.”

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming

And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadows on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore! |

|

George M. Miller. “Valerie, or Minerva.” (Philadelphia, 1814.) Photograph of plaster bust in the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. Poe had few books of his own and was dependent on libraries to ponder over the “many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore” that he would incorporate into a work like “The Raven.” In the poem, the Raven perches on a “pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door.” While putting together this exhibition, we discovered that the Philadelphia Athenaeum had a bust of the goddess Athena (also known as Pallas or Minerva) at that time, and we learned that one “Edgar A. Poe” signed the “Strangers Book” at the Athenaeum on November 19, 1838, introduced by his socially prominent friend Col. William Drayton. |

| |

|

|

Giuseppe Ceracchi. Minerva as the Patroness of American Liberty. (Philadelphia, 1791). Painted terra-cotta. Photograph. |

| |

|

|

Collin Campbell Cooper Jr. A View of the Interior of Library Hall on Fifth Street. (Philadelphia, 1879). Ink, watercolor, wash, and pastel on paper. Most of the titles we know Poe perused were not in the Athenaeum, but they were in the Library Company and available to him even though he was not a shareholder. We have no “stranger’s book,” but it is likely that Poe visited often. Presiding over the reading room was the enormous bust of Minerva by Ceracchi. No reader could miss it; it was the largest object in the place. Though other candidates for the original of the bust of Pallas have been put forward, including one in a Hudson River farmhouse where he once briefly boarded, it is much more likely that Poe was thinking of the ones he saw in Philadelphia, perhaps conflating these two, one “pallid” (though later pewterized) and the other not. |

| |

|

![Henry B[eck]. Hirst. The Book of Cage Birds. Third Edition. (Philadelphia, 1843).](images/th9.4.jpg) |

Henry B[eck]. Hirst. The Book of Cage Birds. Third Edition. (Philadelphia, 1843). Poe originally planned to use a parrot in the poem that became “The Raven,” and it is likely that his best drinking buddy Henry Beck Hirst helped him to this much more magical choice. Hirst operated a bird emporium in Philadelphia and had a tame pet raven. His book is salted with historical and literary allusions, as you would expect from an attorney who was also an accomplished poet. Ravens do not appear, but the book is opened to the section on “Crows – Corvi.” Some varieties, like the jackdaw, “habited in his raven suit,” haunt castle ruins “still mighty in decay, and beneath the parapets of Gothic churches.” A Philadelphia Gothic figure in his own right, Hirst closed his life insane and institutionalized, said to be a victim of absinthe abuse. He insisted to the end that he and Poe wrote “The Raven” together. |

| |

|

|

Edgar Allan Poe. “Barnaby Rudge, by Mr. Dickens,” in Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine. (Philadelphia, February 1842.) As the managing editor of the influential Graham’s Magazine Poe got an audience with Charles Dickens when he visited Philadelphia in 1842. It isn’t difficult to imagine the conversation, since Poe had just reviewed Dickens’s novel Barnaby Rudge, spotlighting among other things the use of a raven muttering prophetic asides. Dickens was also still mourning the demise of his family’s beloved pet raven Grip. (The raven survives – in body if not spirit, stuffed, in Col. Richard Gimbel’s collection at the Free Library.) Poe’s fifteen months at Graham’s made him happy and prosperous at $800 per annum, until he became impatient with non-literary content. The volume displayed also contains “The Masque of the Red Death,” as well as Poe’s important review of Hawthorne’s tales. |

| |

|

![“By ----- Quarles [i.e., Edgar Allan Poe].” “The Raven” in The American Review: A Whig Journal. (New York, February, 1845). Historical Society of Pennsylvania.](images/th9.6.jpg) |

“By ----- Quarles [i.e., Edgar Allan Poe].” “The Raven” in The American Review: A Whig Journal. (New York, February, 1845). Historical Society of Pennsylvania. |

| |

|

|

Edgar A. Poe. The Raven and Other Poems. (New York, 1845). Historical Society of Pennsylvania. After his former magazine Graham’s rejected “The Raven,” Poe sold it to a new Manhattan monthly edited by George Colton, where it appeared under a pseudonym. Its first appearance in book form was this edition in paper wrappers by Wiley and Putnam. When Graham refused “The Raven,” he took up a charity collection for Poe that totaled $15. Colton paid him less than $20 for it. Either of these near-mint first appearances would fetch a price in five figures at auction today. |

NEXT: Cenotaph >

![P. [i.e., Edgar Allan Poe]. To Messrs. Bowen & Gossler, Editors of the “Columbia Spy.” (New-York, June 18 [1844]). Holograph manuscript letter signed.](images/th8.5a.jpg)

![Henry B[eck]. Hirst. The Book of Cage Birds. Third Edition. (Philadelphia, 1843).](images/th9.4.jpg)

![“By ----- Quarles [i.e., Edgar Allan Poe].” “The Raven” in The American Review: A Whig Journal. (New York, February, 1845). Historical Society of Pennsylvania.](images/th9.6.jpg)